Navigating Chess Openings, Part 1

How to travel backward and forward through chess opening variations.

What is a Chess Opening?

Wikipedia states:

“The opening is the initial stage of a chess game. It usually consists of established theory. The other phases are the middlegame and the endgame.[1] Many opening sequences, known as openings, have standard names such as “Sicilian Defense”. The Oxford Companion to Chess lists 1,327 named openings and variants, and there are many others with varying degrees of common usage.”

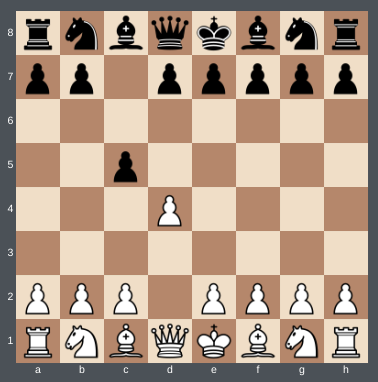

While a good definition, it leaves some ambiguity. One could imagine that a chess opening is sequence of moves that has a name. For example, the move sequence 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 is an opening called the Najdorf Sicilian, named after an Argentine Grandmaster who lived in the last century. The resulting board position is shown:

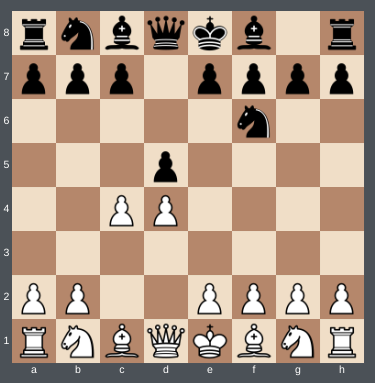

A problem, though, is that sometimes two or more opening move sequences lead to the identical positions. These are call transpositions. Look at the following:

1. d4 d5

1. c4 d5

These are the resulting board positions:

The two lines each have a name. The first is called the Queen’s Pawn Game (1. d4 d5), and the second is the Anglo-Scandinavian variation of the English Opening (1. c4 d5). Now, one more move is played in each line:

1. d4 d5 2. c4

1. c4 d5 2. d4

And this results in the following position (for both lines):

An expert player, looking at the position alone and unaware of the moves played, would readily identify the opening as the Queen’s Gambit, which is considered a subvariation of the Queen’s Pawn Opening, not the Anglo-Scandinavian. But why? It is because the position is far more commonly arrived at by the first line (1. d4 d5 2. c4) rather than the second (1. c4 d5 2. d4).

As for the second line, it is said that the Anglo-Scandinavian has transposed into the Queen’s Gambit. Because of transpositions, it is simpler and less ambiguous to name an opening based on a board position rather than a move sequence.

FEN Strings

Board positions can be recorded using a string of numbers and characters called Forsyth-Edwards Notation (FEN). A FEN string can encode every conceivable arrangement of pieces on a chessboard. Importantly, it can be used to identify one and only one opening.

That’s not to say that any board position has one and only one FEN, as FENs contain more information that just board position. Here’s an example:

This position is commonly referred to as the Marshall Defense. There are two ways to get here:

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 d5

1. d4 d5 2. c4 Nf6

These two lines lead to the same position, but have different FEN strings:

rnbqkb1r/ppp1pppp/5n2/3p4/2PP4/8/PP2PPPP/RNBQKBNR w KQkq - 0 3

rnbqkb1r/ppp1pppp/5n2/3p4/2PP4/8/PP2PPPP/RNBQKBNR w KQkq - 1 3

The second-to-the-last space-separated field in the string indicates the number of moves since the last pawn was moved. This is only ever used to determine if the 50-move rule has been reached, and so doesn’t apply to openings at all. For practical purposes, our main concern is with the first (positional) field of the FEN string when navigating openings. Since all moves sequences lead to a board position, this post will use both interchangeably where there is no ambiguity.

Opening names are not unique, for historical and geographic reasons. Most references call 1.e4 e4 2.Nf3 Nf6 the Petrov Defense, or the Petroff Defense, and a few refer to it as the Russian Defense. Different references will use different names. The closest thing to a standard nomenclature is the Encyclopedia of Chess Openings, which will be covered in the next section.

Not all moves in an opening line get a new name, either; some will inherit the previous move’s opening name. This often happens when a variation has some moves with no viable alternatives — so-called “forced” moves.

The Encyclopedia of Chess Openings

The closest that comes to an official categorization of openings is the Encyclopedia of Chess Openings, a.k.a. ECO. The ECO has five broad categories, abstractly labeled A, B, C, D, and E. Under each category, there are codes 00–99 that have a named move sequence, which is the opening name.

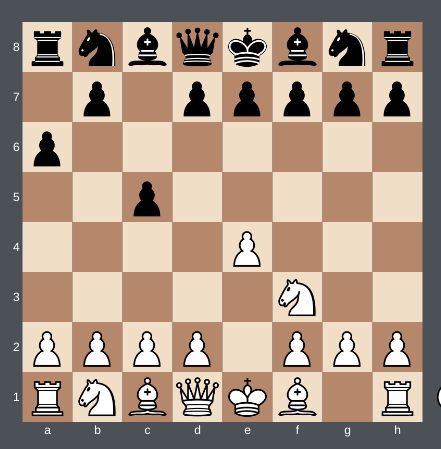

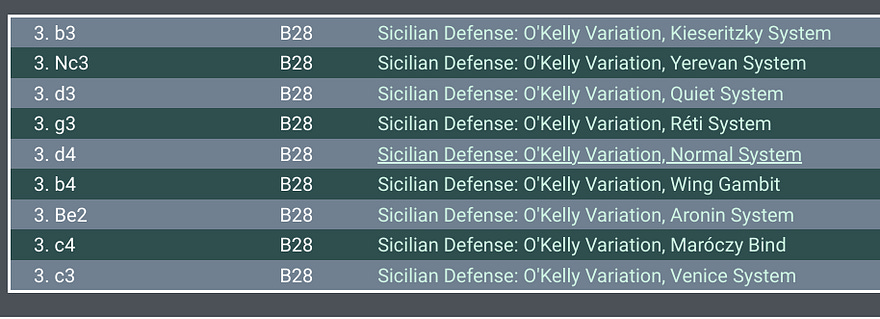

The ECO has been well-curated by chess masters over the course of many decades, so we don’t expect two difference move sequences (as denoted by category and code) to lead to identical positions. For example, ECO code B28 refers to the move sequence 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 a6, naming it the O’Kelly Variation of the Sicilian Defense:

White has many playable continuations:

You’ll notice that ECO codes alone are not specific enough to identify one an only one opening. Every continuation from this point is categorized as B28. ECO has 100 codes for each of the five categories, so there are only 500 codes. There is a root line for each code (the code A00, Irregular Openings being the sole exception), but openings that extend that root line can also share the same code.

While the Encyclopedia of Chess Openings is a standard reference, it is selective in what openings it includes. Other sources may contain offbeat lines that ECO doesn’t have, yet usually those lines have some theory or story behind them, so they’re worth noting for that reason alone. An opening database I contribute to has opening data collated from several reference sources, resulting in over 12,000 unique opening lines. Each of these sources, taken together, overlap, contradict, and complement each other. There are also another 4000 “interpolated” openings, which will be covered in Part 2.

How did we get here? Where can we go?

We saw how both the Anglo-Scandinavian and the Queen’s Pawn Game could wind up at a board position recognized as the Queen’s Gambit. Let’s refer to the Queen’s Pawn Game and the Anglo-Scandinavian as root variations of the Queen’s Gambit. Any opening may have one, two, or more roots. Roots are any sequence of moves that lead to any given position on the board. If the position is a named opening, than all roots should also be named openings. I say should, because there can occur gaps in the opening data, where some in-between position(s) are missing and have to be interpolated, which will discussed in Part 2.

Knowing where you came from is nice, but more often you want to know what next move can be played. Normally, there are dozens of legal moves available, but most of those are bad or mediocre. Only a few will have an opening name associated with the resulting position. There’s a subtle distinction, though, between moves that can be played as a continuation of an opening, and moves that are transpositions from an entirely different opening.

I’ve created an opening database called Fenster that I’ll use to illustrate. After the move sequence 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4, we arrive a variation of the Sicilian Open.

Then next step it to find out what legal moves there are, and if any of those lead to known openings. Moves listed under Next Moves are continuation of the opening line. The line listed under Transpositions, however, invokes the phrase, “You can’t get there from here.” This is because the move sequence of the transposition, while leading to the position shown, is in an order that is not compatible with the current line. The last move in the transposition, 4…d6, cannot be played as a continuation of the current line, because 2…d6 was played earlier. But if Black next plays 4…e6, a move played on move two in the transposition line, then they’ll arrive at the same position as the transposition.

In Part 2, I’ll examine how to fill in the gaps in the opening data we have so far.